![placeholder]()

This presentation was delivered on June 14, 2013, at the BALLE Conference in Buffalo, New York. Download a PDF version of the text.

Welcome, everyone. Thanks for being here. (Slide 2) I’m Stacy Mitchell. I direct the Institute for Local Self-Reliance’s Community-Scaled Initiative, which provides research, policy analysis, and tools to help communities gain greater control over their own economic futures.

Let me begin by offering a little background on this session. (Slide 3) The movement for local economies has grown dramatically over the last decade. We’ve attracted public support and engaged tens of thousands of entrepreneurs and community leaders. But I think we’ve reached a point where we can’t get much further solely with the strategies we’re using now. We’re at a stage where we need to up our game. I want to suggest to you today that moving a policy agenda is a key part of what we need to do.

I’m hoping we can tackle four key questions in this session (Slide 4):

- Why is changing public policy essential to our success?

- How can we frame a compelling narrative for policy change?

- What would be the primary components of our agenda?

- What are the initial steps we need to take?

The format for today is that I’m going to kick off the session by providing some thoughts on each of these questions. Then we’re going to turn to the panel. We have four terrific panelists today: Kimber Lanning of Local First Arizona; David Levine of the American Sustainable Business Council; Micaela Shapiro-Shellaby of the Coalition for Economic Justice here in Buffalo; and Jonathon Welch, owner of Talking Leaves Books, also here in Buffalo. They each have a story to share about a policy win that will help us reflect on some of these themes. And then we’re going to have a roundtable discussion. I’ll be bringing in all of you at that point for what I hope will be a lively conversation. So, with that, let me dive in.

Why is it essential that we work on policy now?

(Slide 5) Let me give you the “good news/bad news” story on where things stand in a few sectors.

Let’s start with food. The good news is that we’ve seen remarkable regeneration of local food systems over the last ten years. (Slide 6) The U.S. is home to 112,000 more small farms today than existed in 2002. (Slide 7) The number of farmers markets has grown from about 3,000 to almost 8,000. (Slide 8) And, perhaps most surprising of all, we’ve added over 1,400 new locally owned small grocery stores, many of which are succeeding by specializing in locally produced food.

(Slide 9) But here’s the bad news. All of this activity is still a very small part of the food system. Locally grown foods, including those marketed directly to consumers and those sold in grocery stores, account for less than 2 percent of the market. (Slide 10) If we look at independent grocers, although they have grown in numbers, their overall market share has shrunk from about 25 to 20 percent in the last decade. Meanwhile, we’ve experienced massive consolidation in the rest of the food system. (Slide 11) Walmart was a small player in the grocery industry 15 years ago, with only about 4 percent of grocery sales. (Slide 12) Today it captures one of every four dollars Americans spend on groceries. (Slide 13) The top 5 supermarket chains have grown from one-quarter of the market to one-half.

(Slide 14) This consolidation among retailers has triggered a wave of mergers among food processing companies, as they try to bulk up to hold their own selling to Walmart. Four meatpackers now account for 85 percent of the nation’s beef. A single dairy company, Dean Foods, processes 40 percent of the milk produced nationally and 70 percent of the milk in New England. (Slide 15) With a single dominant buyer of milk, dairy farmers are struggling to get a fair price. As consumers, we don’t even notice the demise of choice, because Dean Foods markets under dozens of different brands.

So, local food enterprises are flourishing, but they are still a sliver of the market. The rest of the food system, meanwhile, has become more concentrated and industrialized than ever before.

(Slide 16) Or look at banking. On the heels of a massive financial crisis, there was a sudden, widespread public recognition of the fallacies of big banks and a mass movement to shift deposits to local banks and credit unions. Hundreds of thousands, certainly, and probably more like millions, of people have moved their accounts. Credit unions have gained 7 million new members since 2007.

(Slide 17) And, yet, in that same space of time, one of every five locally owned banks and credit unions closed their doors. That’s about 3,000 fewer local financial institutions than we had six years ago. The share of banking assets held by local banks and credit unions has shrunk, as has their share of U.S. deposits. Meanwhile, the largest banks have gained ground and are now bigger than ever. Let me show you what that shift looks like. (Slides 18, 19, 20) Today, giant banks hold 56 percent of bank assets. (Slide 21) If you look closer, in fact, you’ll see that the banking system is largely in the hands of just four banks, each of which has a staggering $2 trillion in assets.

Or consider the independent retail sector. (Slide 22) Independent Business Alliances and Local First campaigns have taken root in over 150 cities. ILSR’s annual Independent Business Survey has consistently found that these initiatives are making a difference. And, indeed, we’ve seen a remarkable reversal of the trends in some key sectors. (Slide 23) There are 249 more independent bookstores today than there were in 2009. (Slide 24) The number of independent fabric stores, pet stores, and small neighborhood food markets has grown.

(Slide 25) And yet, the overall market share of independent retailers continues to fall. Walmart is opening 219 new stores in the U.S. this year and 260 next year. (Slide 26) And the future of retail looks even more ominous. A single company, Amazon, now captures one-third of online orders and is doubling in size every two to three years.

What’s going on? The localism movement is driving real change that we can measure, but it is running up against major structural forces that are moving the economy in the opposite direction. (Slide 27) Chief among those forces are government policies that undermine local businesses and expand corporate power.

Let me give you a few examples. (Slide 28) Since 1995, through the farm bill, the federal government has distributed $275 billion to farmers. Nearly 80 percent of those dollars went to the largest 10 percent of farms in the country. It’s no wonder that a quarter-pounder often costs less than a pound of locally grown broccoli. (Slide 29) Our state and federal tax codes, meanwhile, are littered with loopholes that big corporations can use to escape taxes that their smaller competitors must pay. This modest office building in Wilmington, Delaware, has only a few parking spots, but it’s an address used by hundreds of companies, including Walmart, General Motors, and CVS, as part of a scheme to avoid paying state corporate income taxes. (Slide 30) In the banking sector, as we all know, our response to the financial crisis was to create a slew of programs and policies that bailed out big banks and made it harder for local banks to survive.

Local, state, and federal policy have all conspired to tilt the playing field. My concern is that, if the only way we try to transform the economy is through our individual actions as consumers, investors, and entrepreneurs, local enterprises are going to remain little more than an interesting side-note on the margins of the economy. It’s not that our consumer choices don’t matter. They absolutely do, especially to the local businesses, banks, and farms that count on those dollars. But as consumers we’re too weak to change the larger dynamic. (Slide 31) It’s as though we have to push a giant boulder up a hill. In theory, if we aligned all of our purchasing decisions, we could do it. But that’s a tall order in the real world. It’s a hard way to make change.

(Slide 32) Our real power lies in our citizenship. (Slide 33) We need to use our political muscle as citizens to level the playing field and to make the job of growing local economies easier. We’re much more powerful as citizens than we are as consumers. Corporations know this, which is why they are always talking about us and positioning us as consumers, while weakening our authority as citizens. We need to reclaim our citizenship and start advancing change not just in terms of buying locally or even investing locally, but in joining with our friends and neighbors to remake public policy.

How can we frame a compelling narrative for policy change?

(Slide 34) We need a shared framework and narrative that all of our allied organizations — Local First groups and Independent Business Alliances, as well as national organizations like ILSR — can use to convey our vision for the economy and build momentum for change. By incorporating this shared language across our various campaigns and initiatives, we can begin to make the local economy story part of the public discourse and, as this narrative gains currency, it will in turn strengthen and improve our odds of winning specific policy campaigns.

(Slide 35) To give you an example of what I’m talking about, consider the idea of “limited government,” which has had an enormous impact on policy-making in the last thirty years. We can all explain the basic story of limited government: It’s the idea that if we shrink government and get government out of the way, people and companies will be free to innovate and grow the economy. It’s an idea loaded with powerful values, like freedom. Whether you agree with it or not, it’s a policy narrative that influences many debates over federal regulations, state budgets, and so on.

(Slide 36) We would do well to articulate a similarly bold and value-laden framework for a localist policy agenda. For ILSR, the heart of the story is about community self-determination. It’s about breaking the power that big corporations have over our livelihoods, our democracy, and our environment. It’s about shifting economic activity to locally and cooperatively owned enterprises that are accountable to their communities and operating at a sustainable scale.

(Slide 37) One outcome of this transition would be a more democratic distribution of wealth and income, as well as a richer variety of meaningful jobs, something our current economy fails to deliver. Another would be a dramatic narrowing of the distance between those who make economic decisions and those who feel the impacts, resulting in a more responsible approach to natural systems and the environment. And, finally, it would lead to more resilient communities; in times of rapid change, economic resources that are controlled locally are much more readily marshaled and reconfigured to meet shifting local realities.

For ILSR anyway, that’s the compelling narrative. The challenge is how to best communicate, promote, and advance these ideas. That’s what I’m hoping we can dig into during today’s roundtable conversation and in the open space session that follows.

What would be the primary components of a localist policy agenda?

(Slide 38) Let me suggest seven broad areas of policy change that we need to pursue.

1. Stop Subsidizing the Corporate Economy (Slide 39)

We need a national campaign for a level playing field. Governments provide billions of dollars a year in subsidies and tax advantages for the biggest companies. Most people have only a dim idea of the degree to which this goes on. They assume that local businesses are failing because they can’t compete, but, to a large extent, it’s because the game is rigged.

There are some bright spots. (Slide 40) After many years in which local governments in the Phoenix metro gave multi-million dollar subsidies to shopping mall developers and big-box stores, the state finally passed a policy that effectively bans these subsidies.

(Slide 41) A handful of states in the last few years have adopted combined reporting, which closes a loophole that allows big companies to dodge paying income taxes. (Slide 42) This brings the total number of states that have adopted this policy to about half.

(Slide 43) Last month, the U.S. Senate passed the Marketplace Fairness Act, which would, at long last, extend to large online retailers the same requirement to collect sales taxes that local brick-and-mortar stores are subject to.

We need to draw public attention to and fight to end all of these kinds of inequities in our tax and incentive policies.

2. Restructure the Financial System to Operate at a Community Scale (Slide 44)

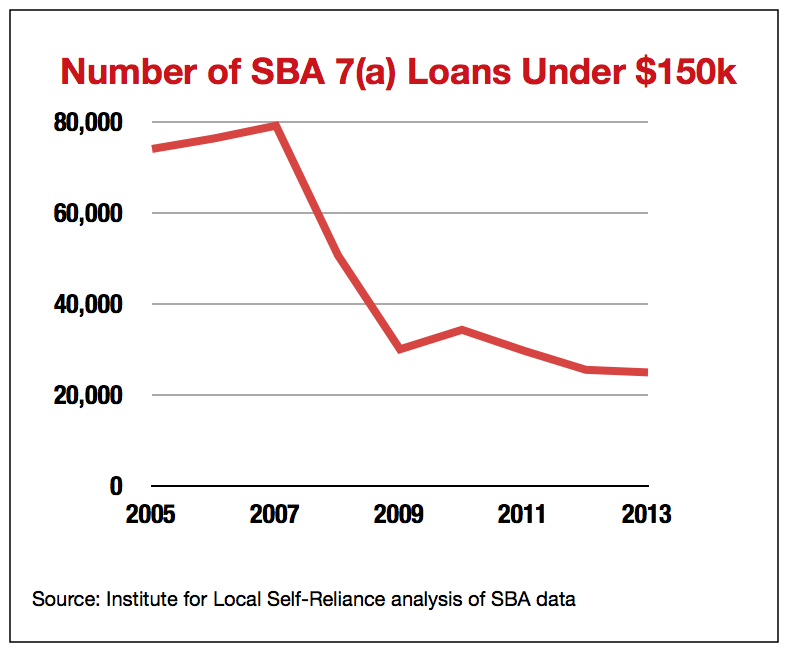

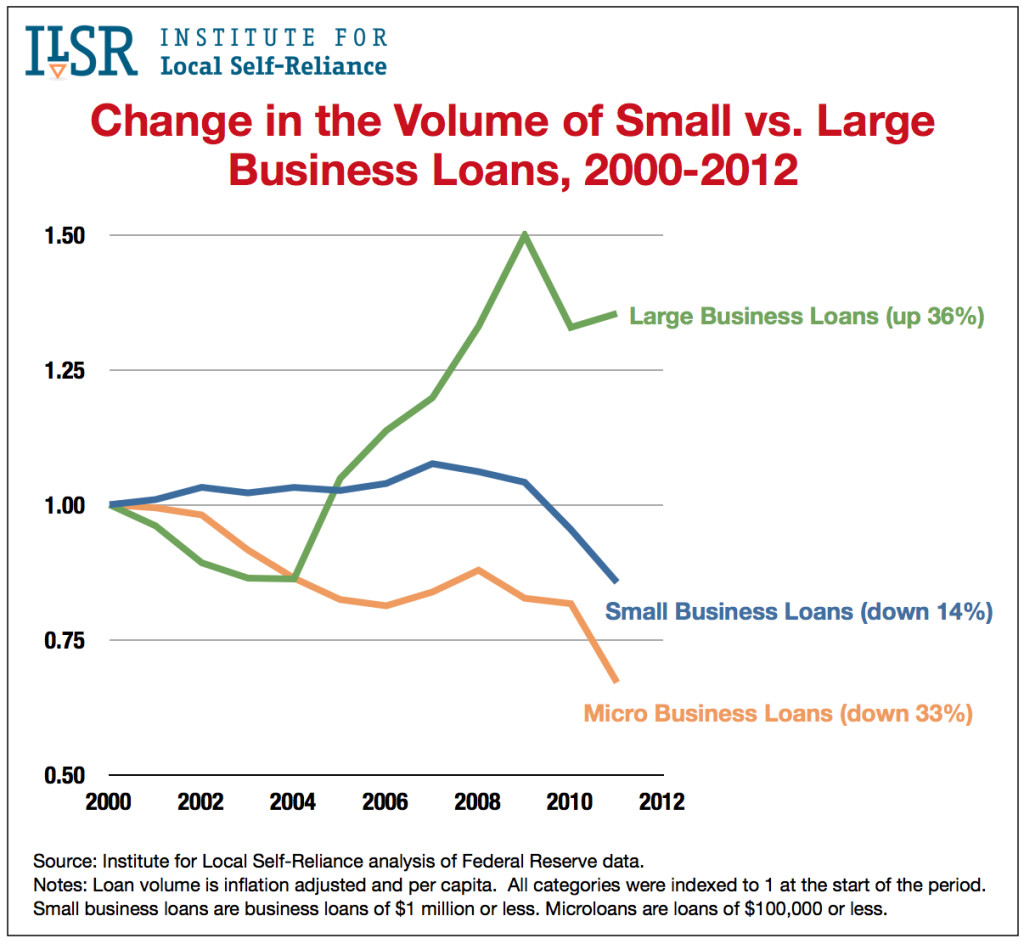

(Slide 45) Right now, we have a banking system that operates at a giant global scale. Not surprisingly, it does a great job of financing giant global corporations, extracting wealth from local communities, and concentrating assets in the hands of a few.

(Slide 46) If we want to regenerate local economies, we need a banking system that operates at a community scale. We need to break up the big banks and return to the decentralized financial sector we had 25 years ago, in which local banks and credit unions held the majority of the assets. In some respects, the policy solutions in this sector are quite simple, because it’s a matter of resurrecting the rules that governed U.S. banking from the 1930s to the 1990s.

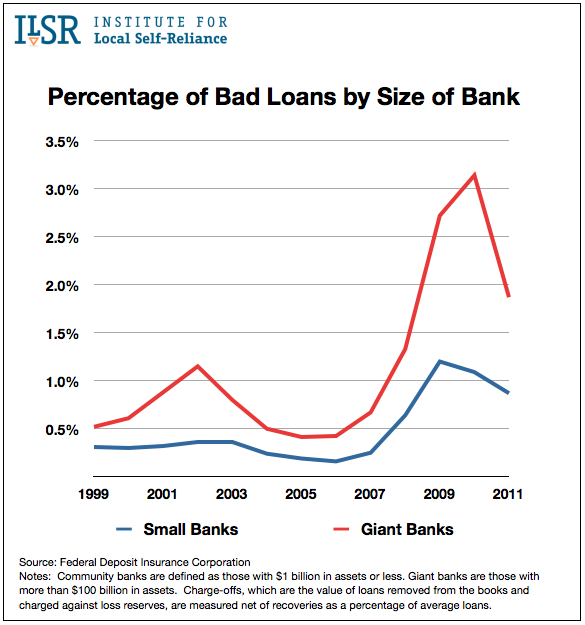

There are many reasons why this is critical. One is that local banks have a mutual interest with their customers. In the words of a community banker in Minneapolis, “We do well when our borrowers do well.” As has recently been made clear, that is not at all the case with big banks. Their own short-term interests very often run directly counter to the interests of their borrowers and customers.

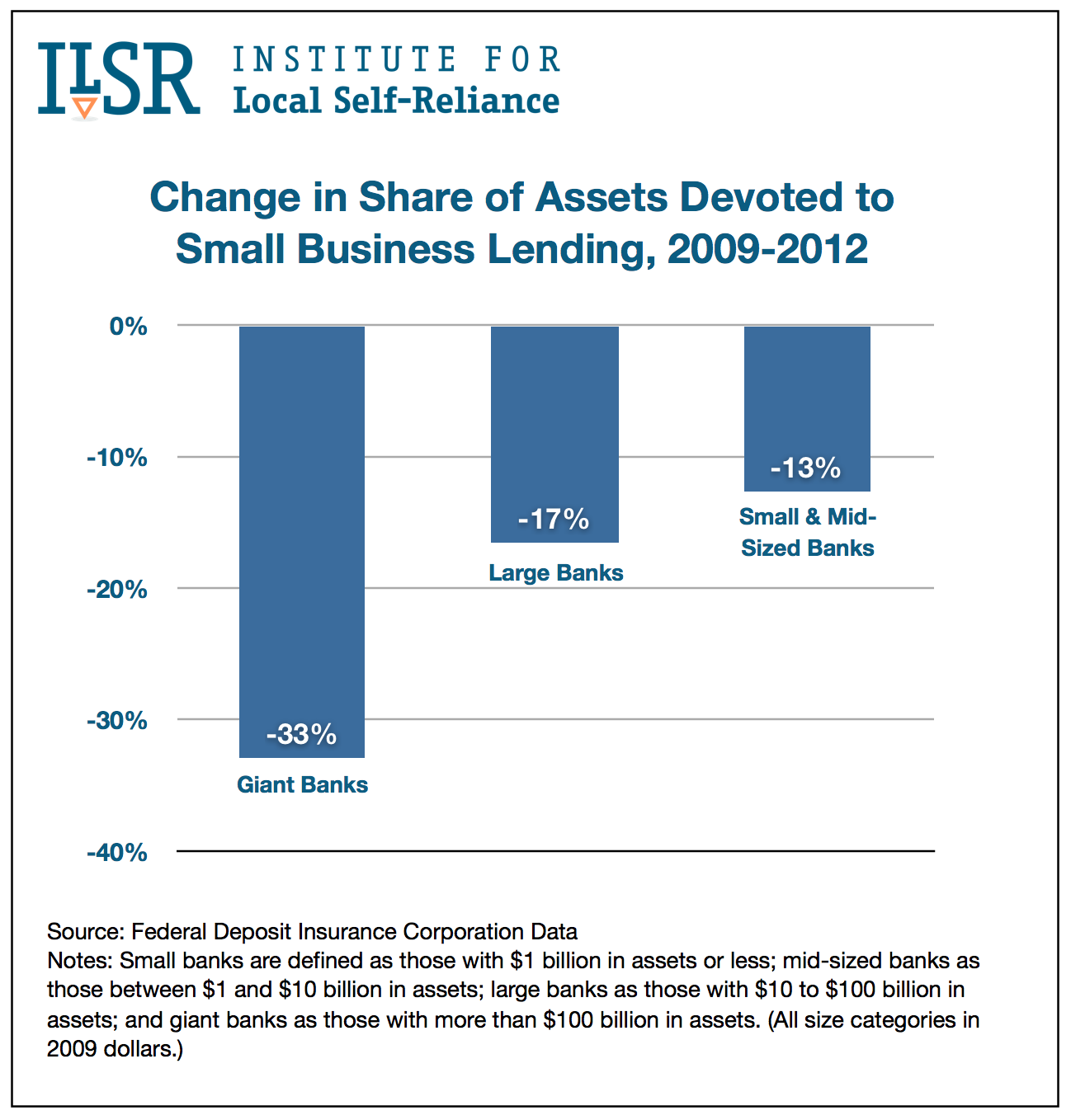

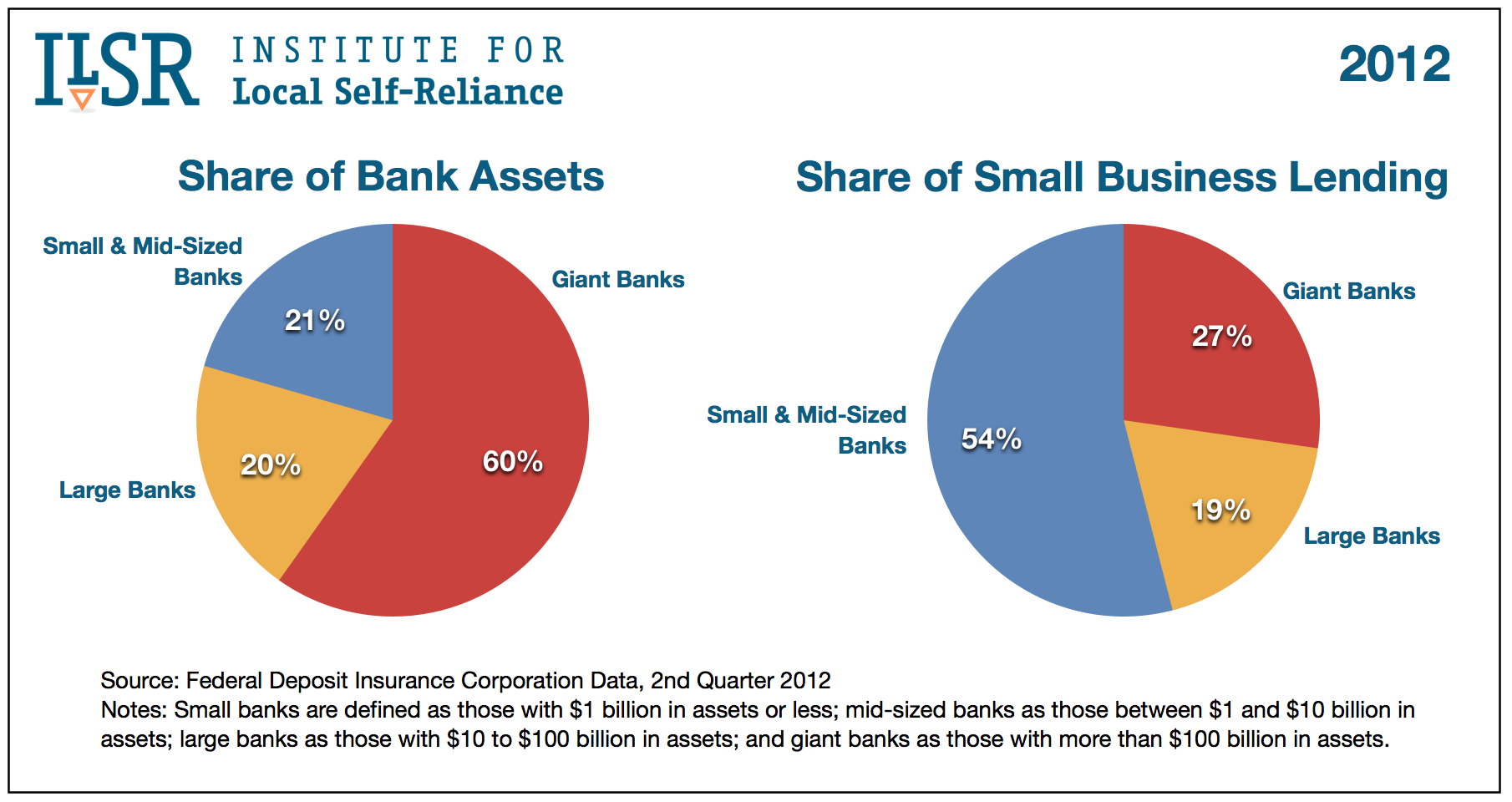

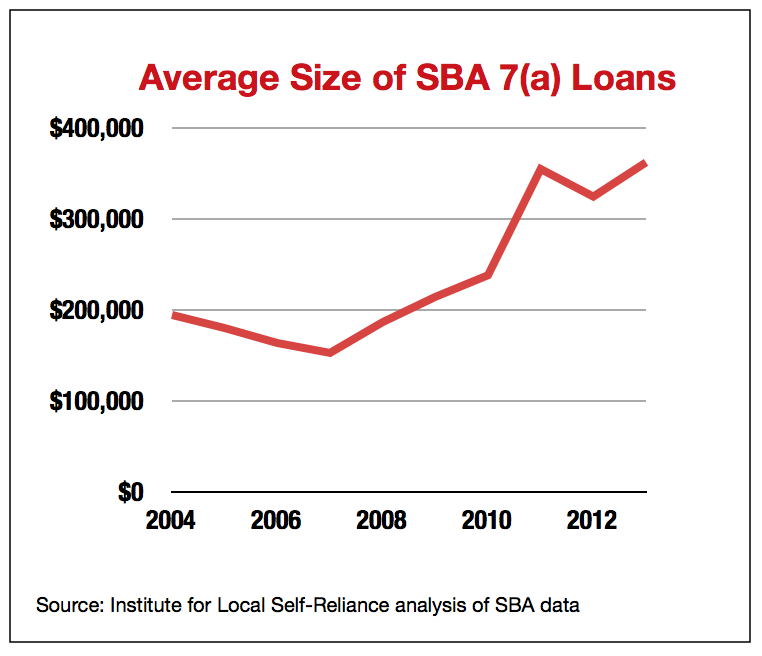

(Slide 47) Another reason is that local banks provide the lion’s share of small business loans. Although small and mid-sized community banks account for only about one-quarter of bank assets, they provide almost 60 percent of small business loans. Big banks hold over half the assets, but provide only about one-quarter of the small business loans. Lacking deep knowledge of local markets and borrowers, big banks have a much harder time accurately judging risk and therefore limit their small business lending.

(Slide 48) In terms of solutions, at the federal level, there’s a bill in Congress that has gathered some support, the Brown-Vitter Bill, which would require big banks to hold more capital and would likely spur the biggest banks to break up.

Several states, meanwhile, are looking at the idea of creating State Partnership Banks, modeled on the Bank of North Dakota. Many of you are probably familiar with the Bank of North Dakota, which uses the state government’s deposits to expand the lending capacity of local banks and provide a secondary market for mortgages. It’s the reason that North Dakota has four times as many local banks per capita as the U.S. as a whole, as well as much more robust local business lending.

At the local level, a growing number of people are beginning to talk about how to establish Local Economy Investment Pools that would allow cities, counties, and other institutions to invest a portion of their funds in financing local economy enterprises and infrastructure.

3. Adopt Planning Policies that Create Great Habitat for Local Businesses (Slide 49)

(Slide 50) Zoning is one of the most powerful tools communities have for shaping the built environment and nurturing the kind of economy they want to see. Indeed, it’s no coincidence that the U.S. cities that have the highest concentrations of independent businesses have zoning rules that protect historic buildings, favor pedestrians and transit over cars, mandate multi-story mixed used buildings, and insist on humanly scaled development. (Slide 51) In cities where zoning rules do the opposite — undermine traditional commercial districts and encourage auto-oriented sprawl — independent businesses are often few and far between.

(Slide 52) Some communities have found other innovative ways to use zoning to support the local economy. San Francisco, for example, has a formula business policy that limits the ability of chains to open in a neighborhood unless they meet specific criteria in the law and have the support of the neighbors. Not surprisingly, the city is home to many more independent grocers, hardware stores, bookstores, and other retailers than other large U.S. cities.

(Slide 53) Another example is Cape Cod. In 1990, voters created the Cape Cod Commission, a regional body composed of representatives of each of the Cape’s fifteen towns. The commission has the authority to review, and reject, large development projects that could significantly impact the local economy or environment, including any commercial building over 10,000 square feet. In order to be approved, the project has to demonstrate that it’s going to be good for the economy. The commission’s decisions are guided by a Regional Policy Plan, which t frowns on development outside of town centers and favors projects that protect the Cape’s character, expand local ownership, and enable the region’s communities to meet more of their own needs instead of relying on imports.

4. Enforce Strong Competition Policies (Slide 54)

(Slide 55) We need to stop allowing big companies to use their size and power to game the market and undermine their local competitors. At various points in our history, we have been called upon to break-up dangerous concentrations of market power, and we now find ourselves at another one of those moments.

For many decades, the primary aim of antitrust policy was to maintain a large number of mostly small businesses and limit concentrations of market power. But this began to change in the 1980s, when antitrust policy became narrowly focused on consumer prices. Antitrust authorities took the position that, as long as a company could deliver lower prices in the short term, it didn’t matter how big it became or how much market power it amassed.

This approach has been a disaster for small businesses and competition. We need to reclaim the original spirit of antitrust policy. Dairy farmers should have a variety of processors competing for their milk. Prescription benefit management companies should not be allowed to force consumers to use a mail-order prescription service owned by the benefit company instead of a community pharmacy. A single retailer should not be allowed to capture half of the grocery market, which is the share Walmart now has in about 40 metro areas. (To give you a sense of how much things have changed, in 1966, the U.S. Supreme Court blocked a merger between two supermarket chains, because together they would have 9 percent of the market in Los Angeles.)

These are all very common-sense statements that would resonate strongly with most Americans and certainly most independent business owners. It’s up to us to start this conversation and build the popular support necessary to chance current policy and enforcement practices.

5. Shift Spending by Public Institutions (Slide 56)

The spending choices of our schools, city agencies, state governments, public universities, public hospitals, and so on should reflect our values and be guided by a principle of maximizing economic outcomes for local communities. That can be accomplished in part by implementing a modest price preference for goods and services produced or provided by local businesses.

6. Make Targeted Local Economy Investments (Slide 57)

There are areas of the country where wealth and resources have been so depleted that simply removing barriers and creating the right environment for local entrepreneurs is not enough. There are also sectors of the economy where key pieces of infrastructure for local production and distribution are missing. Both kinds of gaps need targeted intervention.

(Slide 58) One example of how to do this is the Pennsylvania Fresh Food Financing Initiative. Seeded with $30 million in state money, this loan fund has raised more than $120 million in capital to finance over 80 locally owned grocery stores in low-income urban and rural communities that lacked stores selling fresh food and where conventional bank loans for start-up food retailers were hard to come by. All but one of the businesses financed by this program have been successful.

7. Collect Better Data and Set Benchmarks to Track Progress (Slide 59)

Local and state governments, as well as the federal government, collect lots of data on the economy, but the information they gather and publish is not very useful for tracking the market share of place-based enterprises. Few states could tell you, for example, what share of their food comes from local or regional sources. No state regularly analyzes economic leakages to see where there are opportunities to develop local industries to meet local needs. Many states do not even publish information on the economic development incentives they provide and the outcomes of those giveaways.

Cities, meanwhile, collect information on every business that applies for a license to operate and, yet, no city that I know of could tell you what percentage of its retail space is occupied by locally owned businesses and how that has changed over the last decade. At the federal level, the U.S. Economic Census contains useful data, but it is released so slowly that it’s invariably out-of-date and some of the most relevant data are published only at the national level and not broken down by state or city.

All of this makes it difficult to measure change over time and see the impact of policy changes. We need to direct public agencies to collect better, more relevant data about the economy, which would enable us to establish benchmarks to track progress.

What are the steps we need to take to advance this agenda?

(Slide 60) Let me suggest three fronts as we move forward. First, as I said earlier, I think we need to work together to develop a shared narrative and policy statement that independent business networks and local economy groups can publicize and incorporate into their own activities and campaigns. That’s a process that we’ll begin today in the open-space session and continue in the coming months, inviting other allies who are not here today to join in.

Second, we need hard data to back up this vision for the economy. To this end, we need to continue to build the empirical case for a decentralized economy. We need rock-solid research demonstrating that locally owned, community-scaled enterprises are viable and have the potential to comprise a major share of the economy. This is a significant part of what ILSR does. (Slide 61) We’ve produced, for example, an analysis showing that most states could meet all or most of their energy needs with small-scale renewable power production. (Slide 62) Our research also has shown that the optimal size for a bank, both in terms of efficiency and productive lending, is many times smaller than the giant banks that now dominate our economy.

(Slide 63) Lastly, we need to build power and political capacity among independent business owners and advocates. That’s why the work your organizations are doing to bring independent businesses together to solve their common challenges is so crucial and I hope you’ll join with us in making policy change a central part of your strategy.