A significant share of locally owned businesses are struggling to secure the financing they need to grow. Our 2014 Independent Business Survey found that 42 percent of local businesses that needed a loan in the previous two years had been unable to obtain one. Another survey by the National Small Business Association likewise found that 43 percent of small businesses who had sought a loan in the preceding four years were unsuccessful. Among those who did obtain financing, the survey found, “twenty-nine percent report having their loans or lines of credit reduced in the last four years and nearly one in 10 had their loan or line of credit called in early by the bank.”

Very small businesses (under 20 employees), startups, and enterprises owned by minorities and women are having a particularly difficult time. Even with the same business characteristics and credit profiles, businesses owned by African-Americans and Latinos are less likely to be approved for loans and face greater credit constraints, particularly at start-up, according to one recent study.

One consequence of this credit shortage is that many small businesses are not adequately capitalized and thus are more vulnerable to failing. Moreover, a growing number of small businesses are relying on high-cost alternatives to conventional bank loans, including credit cards, to finance their growth. In 1993, only 16 percent of business owners reported relying on credit cards for financing in a federal survey. By 2008, that figure had jumped to 44 percent.

The difficulty small businesses are having in obtaining financing is a major concern for the economy. Historically, about two-thirds of net new job creation has come from small business growth. Studies show locally owned businesses contribute significantly to the economic well-being and social capital of communities. Yet, the number of new start-up businesses has fallen by one-fifth over the last 30 years (adjusted for population change), as has the overall number and market share of small local firms. Inadequate access to loans and financing is one of the factors driving this trend.

Sources of Small Business Financing

Unlike large corporations, which have access to the equity and bond markets for financing, small businesses depend primarily on credit. About three-quarters of small business credit comes from traditional financial institutions (banks and credit unions). The rest comes primarily from finance companies and vendors.

At the beginning of 2014, banks and credit unions had about $630 billion in small business loans — commonly defined as business loans under $1 million — on their books, according to FDIC. “Micro” business loans — those under $100,000 — account for a little less than one-quarter of this, or about $150 billion. (One caveat about this data: Because of the way the FDIC publishes its data, this figure includes not only installment loans, but credit provided through small business credit cards.)

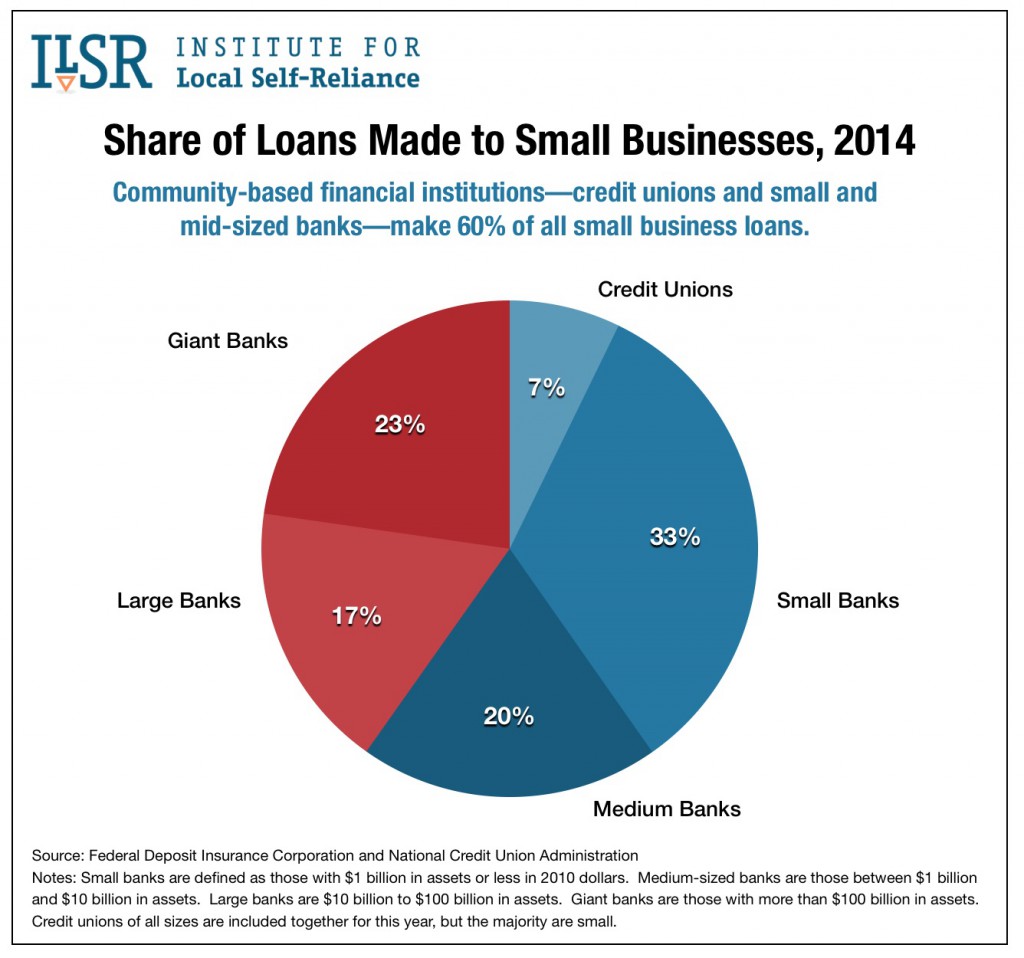

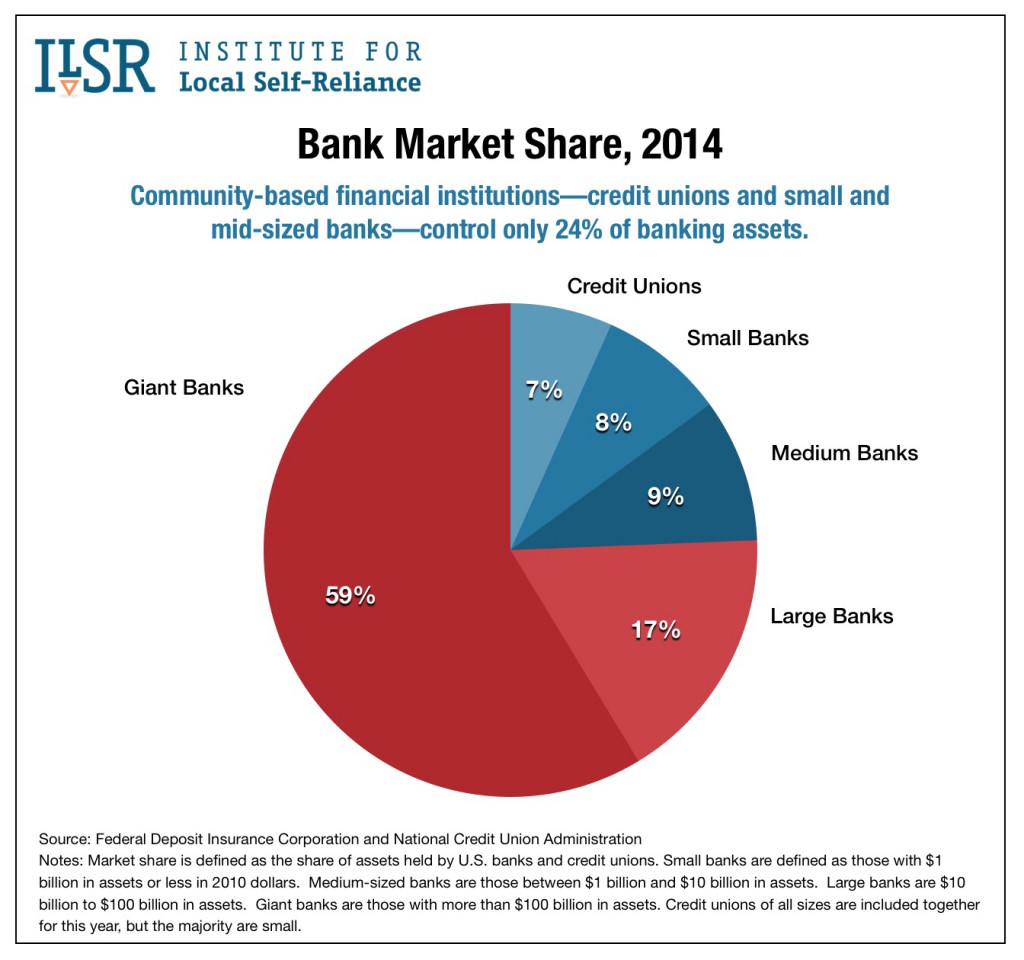

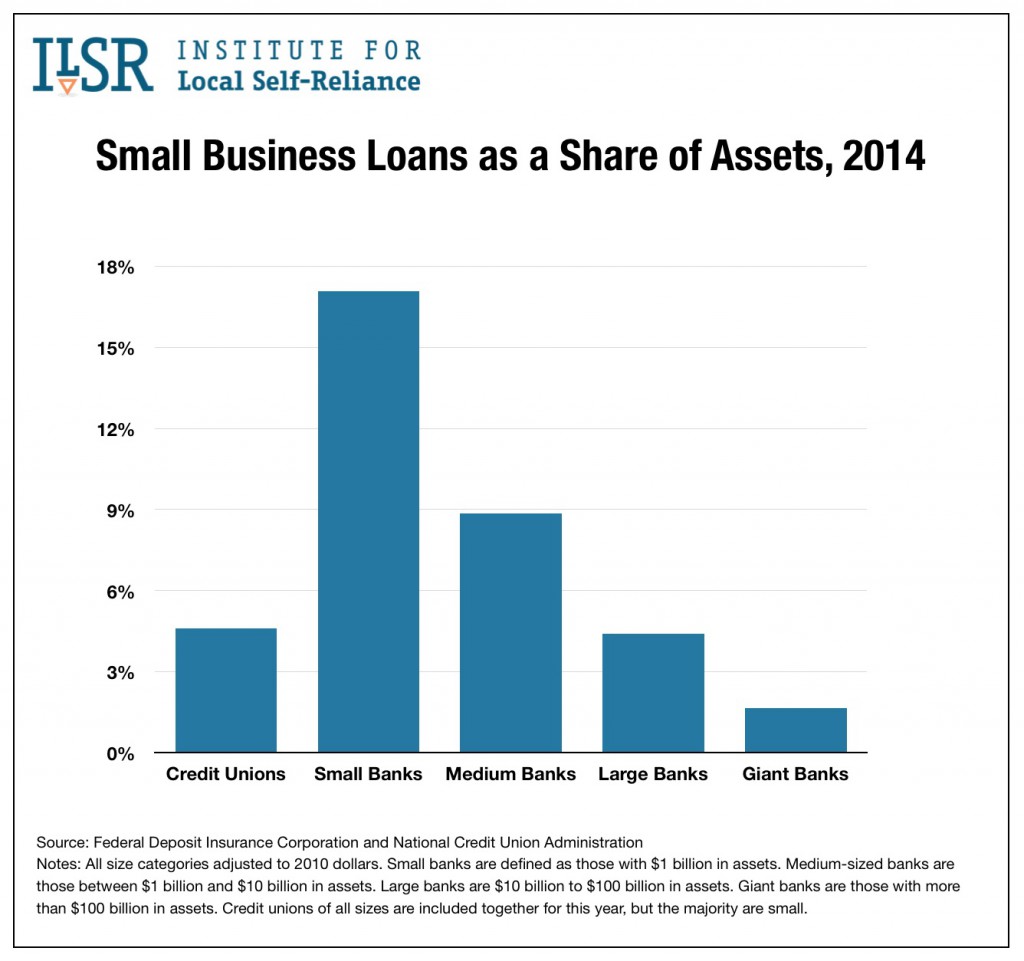

Banks provide the lion’s share of small business credit, about 93 percent. But there is significant variation in small business lending based on bank size. Small and mid-sized banks hold only 21 percent of bank assets, but account for 54 percent of all the credit provided to small businesses. As bank size increases, their support of small businesses declines, with the biggest banks devoting very little of their assets to small business loans. The top 4 banks (Bank of America, Wells, Citi, and Chase) control 43 percent of all banking assets, but provide only 16 percent of small business loans. (See our graph.)

Credit unions account for only a small share of small business lending, but they have expanded their role significantly over the last decade. Credit unions had $44 billion in small business loans on their books in 2013, accounting for 7 percent of the total small business loan volume by financial institutions. That’s up from $13.5 billion in 2004. Although small business lending at credit unions is growing, only a minority of credit unions participate in this market. About two-thirds of credit unions do not make any small business loans.

Crowd-funding has garnered a lot of attention in recent years as a potential solution to the small business credit crunch. However, it’s worth noting that crowd-funding remains a very modest sliver of small business financing. While crowd-funding will undoubtedly grow in the coming years, at present, it equals only about one-fifth of 1 percent of the small business loans made by traditional financial institutions. Crowd-funding and other alternative financing vehicles may be valuable innovations, but they do not obviate the need to address the structural problems in our banking system that are impeding local business development.

Shrinking Credit Availability for Small Businesses

Since 2000, the overall volume of business lending per capita at banks has grown by 26 percent (adjusted for inflation). But this expansion has entirely benefited large businesses. Small business loan volume at banks is down 14 percent and micro business loan volume is down 33 percent. While credit flows to larger businesses have returned to their pre-recession highs, small business lending continues to decline and is well below its pre-recession level. Growth in lending by credit unions has only partially closed this gap.

Since 2000, the overall volume of business lending per capita at banks has grown by 26 percent (adjusted for inflation). But this expansion has entirely benefited large businesses. Small business loan volume at banks is down 14 percent and micro business loan volume is down 33 percent. While credit flows to larger businesses have returned to their pre-recession highs, small business lending continues to decline and is well below its pre-recession level. Growth in lending by credit unions has only partially closed this gap.

There are multiple factors behind this decline in small business lending, some set in motion by the financial crisis and some that reflect deeper structural problems in the financial system.

Following the financial collapse, demand for small business loans, not surprisingly, declined. At the same time, lending standards tightened dramatically, so those businesses that did see an opportunity to grow during the recession had a harder time gaining approval for a loan. According to the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency’s Survey of Credit Underwriting Practices, banks tightened business lending standards in 2008, 2009, and 2010. In 2011 and 2012, lending standards for big businesses were loosened, but lending standards for small businesses continued to tighten, despite the beginnings of the recovery. These tightened standards were driven in part by increased scrutiny by regulators. In the aftermath of the financial crisis, regulators began looking at small business loans more critically and demanding that banks raise the bar. Many small businesses also became less credit-worthy as their cash flows declined and their real estate collateral lost value.

All of these recession-related factors, however, do not address the longer-running decline in small business lending. Fifteen years ago, small business lending accounted for half of bank lending to businesses. Today, that figure is down to 29 percent. The main culprit is bank consolidation. Small business lending is the bread-and-butter of local community banks. As community banks disappear — their numbers have shrunk by nearly one-third over the last 15 years and their share of bank assets has been cut in half — there are fewer lenders who focus on small business lending and fewer resources devoted to it.

It’s not simply that big banks have more lucrative ways to deploy their assets. Part of the problem is that their scale inhibits their ability to succeed in the small business market. While other types of loans, such as mortgages and car loans, are highly automated, relying on credit scores and computer models, successfully making small business loans depends on having access to “soft” information about the borrower and the local market. While small banks, with their deep community roots, have this in spades, big banks are generally flying blind when it comes to making a nuanced assessment of the risk that a particular local business in a particular local market will fail. As a result, compared to local community banks, big banks have a higher default rate on the small business loans they do make (see this graph) and a lower return on their portfolios, and they devote far less of their resources to this market.

More than thirty years of federal and state banking policy has fostered mergers and consolidation in the industry on the grounds that bigger banks are more efficient, more effective, and, ultimately, better for the economy. But banking consolidation has in fact constricted the flow of credit to the very businesses that nourish the economy and create new jobs.

SBA Loan Guarantees Shifting to Larger Businesses

One small but important part of the small business credit market are loans guaranteed by U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA). The goal of federal SBA loan guarantees is to enable banks and other qualified lenders to make loans to small businesses that fall just shy of meeting conventional lending criteria, thus expanding the number of small businesses that are able to obtain financing. These guarantees cost taxpayers relatively little as the program costs, including defaults, are covered by fees charged to borrowers.

One small but important part of the small business credit market are loans guaranteed by U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA). The goal of federal SBA loan guarantees is to enable banks and other qualified lenders to make loans to small businesses that fall just shy of meeting conventional lending criteria, thus expanding the number of small businesses that are able to obtain financing. These guarantees cost taxpayers relatively little as the program costs, including defaults, are covered by fees charged to borrowers.

The SBA’s flagship loan programs is the 7(a) program, which guarantees up to 85 percent of loans under $150,000 and up to 75 percent of loans greater than $150,000 made to new and expanding small businesses. The SBA’s maximum standard loan under the 7(a) program is $5 million, raised from $2 million in 2010. The SBA’s other major loan program is 504 program, which provides loans for commercial real estate development for small businesses. Under these two programs, the SBA approved loans valued at $23 billion in 2013, amounting to 3.7 percent of small business lending. (The 7(a) program accounts for almost 80 percent of this.)

Although the SBA’s loan guarantees account for a small share of overall lending, they play a disproportionate role in credit access for some types of small businesses. According to a 2008 analysis by the Urban Institute, compared to conventional small business loans, a significantly larger share of SBA-guaranteed loans go to startups, very small businesses, women-owned businesses, and minority-owned businesses.

SBA loans also provide significantly longer terms, which improve cash flow and thus can make the difference between success and failure. More than 80 percent of 7(a) loans have maturities greater than 5 years, and 10 percent have maturities greater than 20 years. This compares to conventional small business loans, almost half of which have maturities of less than a year and fewer than one in five have terms of five years or more.

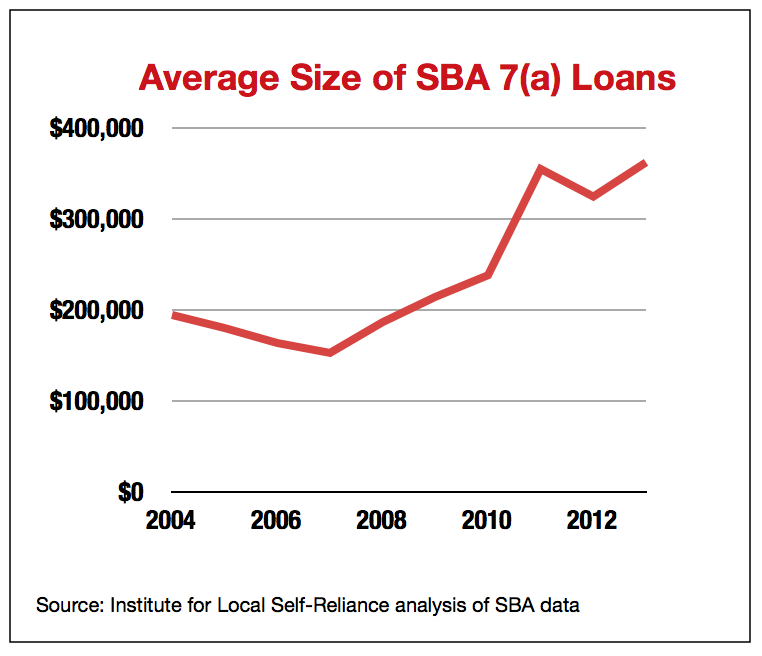

Given the unique and important role of SBA loans, recent trends are alarming. Over the last few years, the SBA has dramatically reduced its support for smaller businesses and shifted more of its loan guarantees to larger small businesses. (The SBA’s definition of a “small” business varies by sector, but can be quite large. Retailers in certain categories, for example, can have up to $21 million in annual sales and still be counted as small businesses.) The number of 7(a) loans under $150,000 has declined precipitously. In the mid 2000s, the SBA guaranteed about 80,000 of these loans each year, and their total value accounted for about 25 percent of the loans made under the program. By 2013, that had dropped to 24,000 loans comprising just 8 percent of total 7(a) loan volume. Meanwhile, the average loan size in the program doubled, from $180,000 in 2005 to $362,000 in 2013.

Given the unique and important role of SBA loans, recent trends are alarming. Over the last few years, the SBA has dramatically reduced its support for smaller businesses and shifted more of its loan guarantees to larger small businesses. (The SBA’s definition of a “small” business varies by sector, but can be quite large. Retailers in certain categories, for example, can have up to $21 million in annual sales and still be counted as small businesses.) The number of 7(a) loans under $150,000 has declined precipitously. In the mid 2000s, the SBA guaranteed about 80,000 of these loans each year, and their total value accounted for about 25 percent of the loans made under the program. By 2013, that had dropped to 24,000 loans comprising just 8 percent of total 7(a) loan volume. Meanwhile, the average loan size in the program doubled, from $180,000 in 2005 to $362,000 in 2013.

What has caused this dramatic shift is not entirely clear. The SBA claims it has tried to structure its programs to benefit the smallest borrowers. Last October, it waived fees and reduced paperwork on loans under $150,000. But critics point to recent policy changes, including lifting the 7(a) loan cap from $2 million to $5 million in 2010. The move, which large banks advocated, has helped drive the average loan size up and the number of loans down.

Policy Solutions

1. Reduce Concentration in the Banking Industry

Rather than allowing a handful of big banks to continue to increase their market share, which would result in even less credit for small businesses and other productive uses, federal and state lawmakers should adopt policies to downsize the biggest banks. Approaches could include resurrecting deposit market share caps, forcing a full separation of investment and commercial banking, and imposing transaction taxes on financial speculation.

2. Expand Community Banks

Policymakers should also enact policies to strengthen and expand community banks, which currently provide more than half of small business lending. At the state level, the Bank of North Dakota provides an excellent model of how a publicly owned wholesale bank can significantly boost the numbers and market share of small private banks, and, in turn, expand lending to small businesses. At the federal level, regulators should address the disproportionate toll that regulations adopted in the wake of the financial crisis are taking on small banks and look to increase new bank charter approvals, which have plummeted in recent years.

3. Allow Credit Unions to Make More Small Business Loans

Current regulations limit business loans to no more than 12.5 percent of a credit union’s assets. Although some have called for lifting this cap, ILSR favors another proposal, which would exempt loans to businesses with fewer than 20 employees from the cap. This would ensure that new credit union lending benefits truly small businesses, rather than simply allowing a few large national credit unions (the only ones close to hitting the current cap) to increase large business loans.

4. Reform SBA Loan Guarantee Programs

The Obama Administration should return to the previous size cap of $2 million on 7(a) loans and adopt other reforms to ensure that federal loan guarantees provide more support to very small businesses. The SBA should also shift a share of of its loan guarantees into programs that are designed primarily or exclusively to work with small community banks.

5. Create Public Loan Funds that Target Key Needs

Although not a substitute for comprehensive restructuring of the banking system to better meet the needs of small businesses and local economies, public loan funds can address specific credit needs. A good example of this is the Pennsylvania Fresh Food Financing Initiative, which has financed about 100 independent grocery stores in low-income, underserved communities.